This article originally ran under a different banner/website in September of 2019 and is now being here re-uploaded for purposes of convenience and consolidation. Please enjoy.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN!!! I CAN’T SHAKE THE FEELING THE GAMES INDUSTRY IS MOCKING ME. 2K Games is mocking my stance against loot boxes with NBA 2K20 being littered with loot boxes, plinko machines, roulette wheels, and slot machines. Now The Sinking City is mocking me with its depiction of Doomsayers. As I, the Video Game Doomsayer, walk the streets of Oakmont, I ran into a half-naked, tattooed man, standing on a soapbox droning on incoherently about how Cthulu is awakened and will claim us all. It feels oddly familiar to when I stand on my soapbox and rant about games devolving into live services and sandboxes. However, your mocking backfires when you also perform the same actions I warn against in an effort to make me look like a deranged lunatic. Almost fittingly, the game on today’s chopping block, The Sinking City, is a Lovecraftian horror game that also tries to be a sandbox game. Better luck next time, games industry.

Our story begins with our hero, Charles Reed, venturing to Oakmont, Massachusetts to seek the answers behind his horrid dreams. He is soon entangled in a web of conflicting ruling families, numerous cult fanatics, and an alarming rate of missing people. Reed is forced to sift through the madness to reach the truth before he reaches the edge of his sanity.

You’d be correct in assuming that The Sinking City is inspired by the works of H.P. Lovecraft, in fact, you could almost view The Sinking City as Lovecraft’s greatest hits. It pulls from The Call of Cthulhu, At the Mountain of Madness, and The Shadow over Innsmouth to create a blend of fairly standard Lovecraftian world. Unfortunately, the missing ingredient in this murky soup of a game is horror. While The Sinking City had some tense moments, I never felt the same fear I had while wandering the abandoned Raccoon City Police Department or the USG Ishimura. While the USG Ishimura forces me into tight claustrophobic space, The Sinking City allows you to freely roam Oakmont, just as you would a city in any Grand Theft Auto title. The game surrenders the story’s pacing when I can choose to stand around and harass random NPC’s by bumping into them rather than continuing with the story.

The Sinking City does try to keep the appearance of a horror game to serve the Lovecraftian name. Frequently, you will be ambushed by Lovecraftian monstrosities that remind me of rigidity plastic knock-offs of the Necromorphs from Dead Space, but with less variety. You have small spindly ones that try to sidestep every shot, one that stands in the back spitting at you, ones that leap at you but look like they are siding on the floor, and of course, the monstrous brute that soaks way too many bullets. Left 4 Dead has a wider variety of monsters than The Sinking City. I’ll admit, these monsters are more enjoyable to fight than humans. Seems like every gangster or cultist has a shotgun that allows them to take chunks of your health bar at the snap of their fingers. Firing any of the guns feels like children’s toys that make snap sounds when the trigger is pulled. The impact always feels minimal as enemies barely react to getting shot. Both humans and monsters can easily overwhelm you since combat is stiff and awkward. You could use the traps and grenades to deal with groups, but Reed always takes centuries to lay a trap or throw a grenade. Some horror games make combat feel uncomfortable to make the player more vulnerable. The Sinking City is clearly aiming for this idea but makes the combat flimsy, lifeless, and unenjoyable.

Here’s the thing, my followers, even though I have been raking The Sinking City over a hotbed of my rage, I feel weirdly absorbed by it. One could assume it is the overwhelming cosmic pull from the old Gods dwelling deep below Oakmont that keeps me coming back to The Sinking City. While I am not discounting cosmic forces, I am more willing to bet on the detective mechanics being what really drew me in. Lately, I have been describing The Sinking City as L.A. Noire with a Lovecraftian style dripping over the city. While combat feels like a token nod to the open-world design, the detective mechanics are where the meat of the gameplay is.

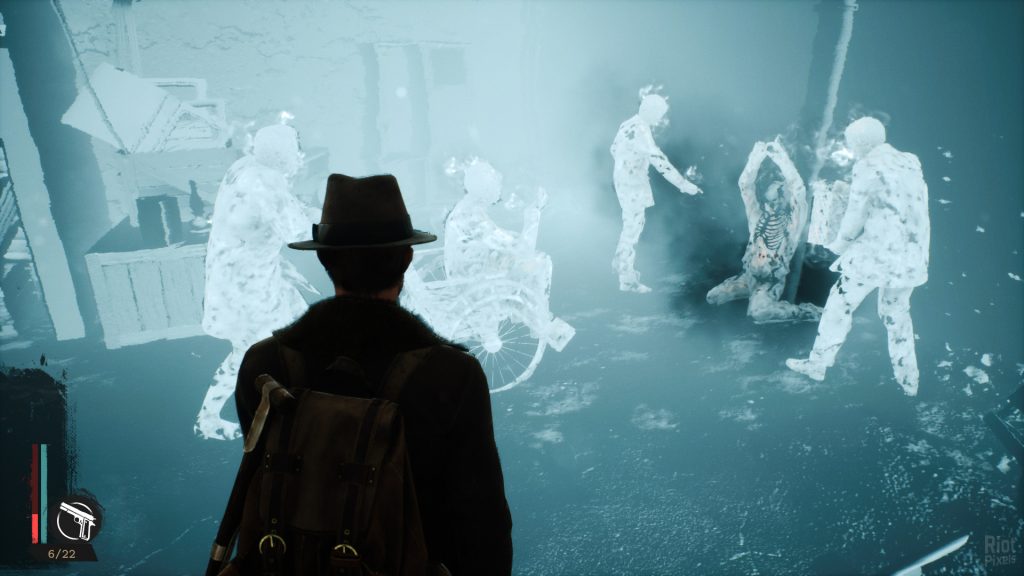

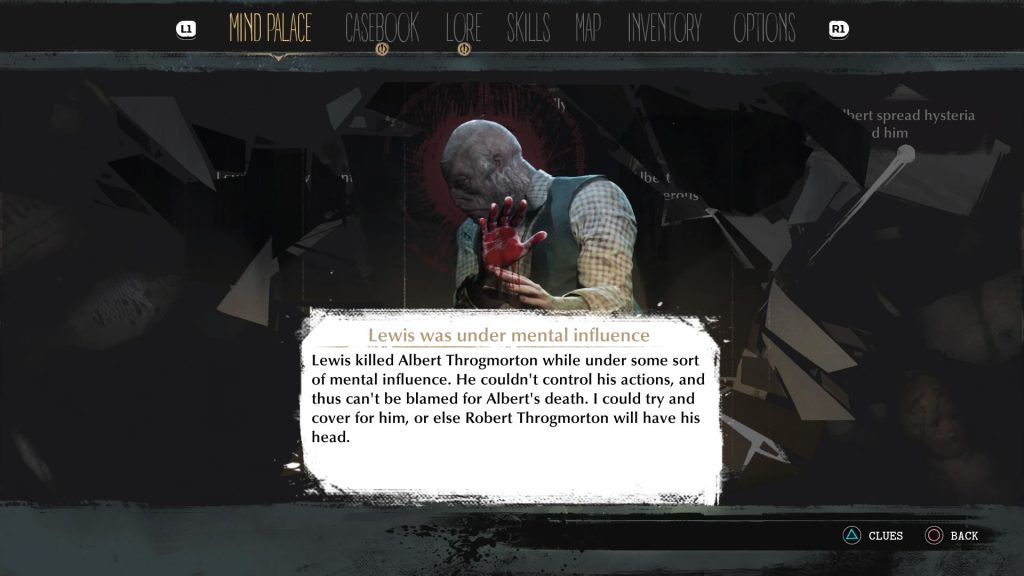

Upon reaching a crime scene, you are immediately tasked with searching for clues. You can pick up objectives and spin them around like most games involving mysteries. You can also activate a Batman-like detective vision called the Mind’s Eye. While you could write off the Mind’s Eye as I did, it’s mostly used to see past events as if an eldritch god is feeding you images designed to make you go mad, which feels thematically fitting. Once you have collected all the evidence, a portal will be revealed that will show you brief snapshots of the crime. Once you correctly order these snapshots, Reed will form clues that you can access in a menu called the Mind’s Palace. Within the fancy-named menu screen, you can piece together clues to form deductions and leads to follow. While these might not be new for developers Frogware, the developers behind the Sherlock Holmes game series, they do a fascinating job immersing you in the life and mindset of a detective.

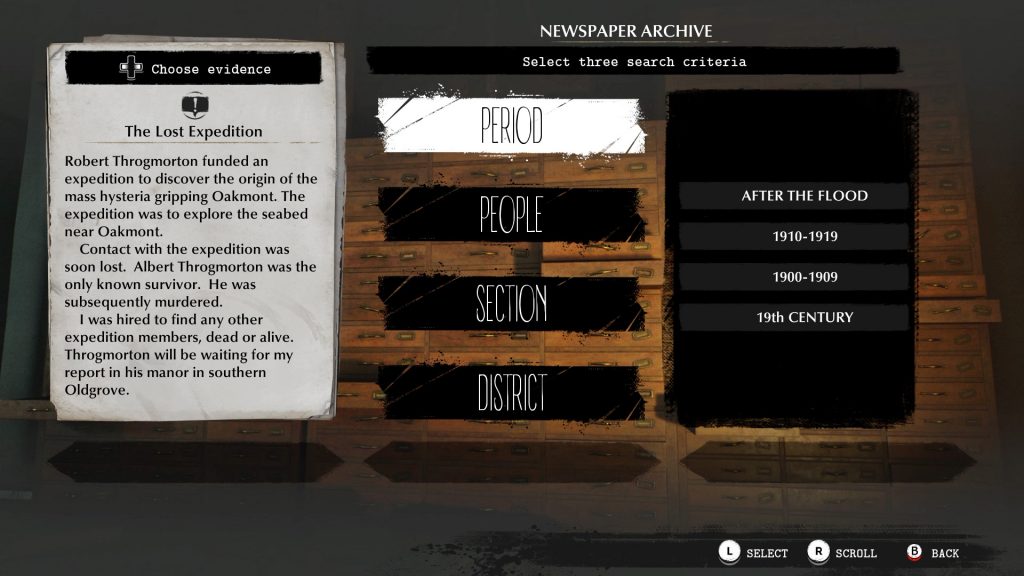

In a more traditional game, you will be given the exact direction to follow the lead, but not in The Sinking City. While that might feel like a problem, it enhances the detective feel. The leads from the crime scene will hint that you require more information that could be obtained through various archives located at town hall, police station, newspaper, or hospital. For example, if you have a lead that a witness was injured when they witnessed the crime, you can use that evidence to determine who your witness is. You take a piece of evidence and cross-check it with a couple of search criteria including location, time periods, and subject matter. Much like gathering evidence, it works really well at engrossing you in the detective work.

The information you gathered from the archives will give the next bread crumb in the form of an address. While most open-world games will plunk a big waypoint on your map indicating where to go, The Sinking City does not. You have to go into the map with the information you collected and set your own waypoint. Again this idea on paper seems daunting and cumbersome, but it really helped me get drawn into The Sinking City.

Having to be my own navigator also helped delay the usual open-world fatigue that I normally experience. I often say an open-world game can be judged by how often I use the fast travel system. Marvel’s Spider-Man’s web-slinging was so electrifying that I never used the fast travel system. Whereas biking round in Day’s Gone was so mind-numbing, I pretty much fast traveled everywhere. The Sinking City falls somewhere in the middle. I spent a large chunk of this game, wandering the streets of Oakmont in astonishment. The Lovecraftian atmospheric layer was enough for me to want to see what was lurking around different corners. Early on, I discovered numerous streets had been flooded and had to be traversed with a motorboat that luckily always appears in whatever street you’re traveling. I remember seeing a once-great momentum, run down and half-sunken into the murky waters.

Unfortunately, after seeing most of the city, you start to notice the copying and pasting. Many of the buildings have similar layouts and you can find copies of NPCs that you can’t interact with within multiple districts. You often find a road blocked off by an Infected Area, a small arena with infinitely respawning enemies, which will force you to take long detours. Towards the end, I was more interested in solving cases than exploring the city and choose to use the Tardis-like phone booths for fast traveling.

The Sinking City is your very typical Eurojank game. To those unfamiliar with the term, this may seem like an insult, but I assure you it is not. Eurojank games are one with really great ideas, sometimes too many ideas, which run out of time or money resulting in them being buggy, obtuse and janky usually from Eastern European teams. While these games aren’t perfect, I often find that they have one brilliant idea utterly unique and worth pushing through the weaker parts. One initial conclusion could be a detective game shackled to a weak combat engine might be The Sinking City’s downfall, but I am not sure I agree. The Lovecraftian open-world certainly has its baggage with the token crafting, character upgrades, and Amnesia-style sanity meter. The Sinking City’s baggage, like most Eurojank games, will be the make or break on an individual level, and while I wouldn’t say it is great, The Sinking City’s baggage didn’t prevent me from getting to the bottom of Oakmont’s mysteries. If you are looking for an inoffensive game, one designed to have zero flaws but zero personality as well, then look to the torrent of live services the game industry trots out. If you are looking for a unique game and are willing to look past warts, I encourage you to give The Sinking City the opportunity to draw you into its murky waters.